Ancient Egyptian sculpture was closely connected with Egyptian architecture and mainly concerned temples and funeral tombs.

Egyptian tombs required the widest use of sculpture. In these pits, portrait statues of the deceased pharaoh were installed. In addition, this type of prehistoric sculpture included statues of civil servants and scribes, as well as groups depicting a man and his wife. The walls of earlier Egyptian tombs resemble, in fact, an illustrated book about the customs of the population.

Illustrative scenes include activities, such as hunting, fishing, and farming; artistic and commercial occupations, for example, making statues, glass or metal products or building pyramids; women doing household chores, or crying for the dead; boys being engaged in sports. Such reliefs show confident belief in the future as a sort of unruffled expansion of the present life. In later periods of Egyptian art, beginning with the tombs of the New Empire, in judgment scenes gods are more noticeable, which indicates smaller confidence in the success of the future state.

Sculptural Materials and Tools

In valley of the Nile, there grew sacred acacia and sycamore, which were the materials for statues and sarcophagi, thrones and other items of industrial art. The slopes on both banks of the Nile supplied sculptors with coarse nummulitic limestone, and outside Edfou there were extensive sandstone quarries. Both materials were used for both sculptural and architectural purposes.

Next to the first threshold, we can still see red granite quarries, used not only for obelisks but also for huge statues, sphinxes, and sarcophagi. Alabaster was mined in the ancient city of Alabastron near the modern village of Assiout. Basalt and diorite came from the mountains of the Arabian desert and the Sinai Peninsula, which were used by early sculptors. Red porphyry was especially appreciated by the Greeks and Romans, as well as copper.

Even mud from the Nile River was molded, burned, and covered with colored gloss. During that same early period, we see that the Egyptian sculptor deftly copes with numerous imported materials, such as ebony, ivory, iron, gold, and silver. For example, ivory carving was widely used in the Chryselephantine sculpture for major works.

When Egyptian sculptors wanted to add extra resilience to their sculptures, for example, statues and sarcophagi of the pharaohs, they used the hardest materials, such as basalt, diorite, and granite. These hard stones were treated with the same skill as softer stones and wood and ivory.

Finer details were, probably, applied with the help of flint instruments. Other tools made from hardened iron or bronze were tubular drills of various types, saw jeweled teeth, chisel and pointer. Statues of hard stone were carefully treated with emery and crushed sandstone; softer stonework was usually covered with stucco and painted, and the pigment was applied in a conventional or arbitrary way.

Egyptian Statues and Their Features

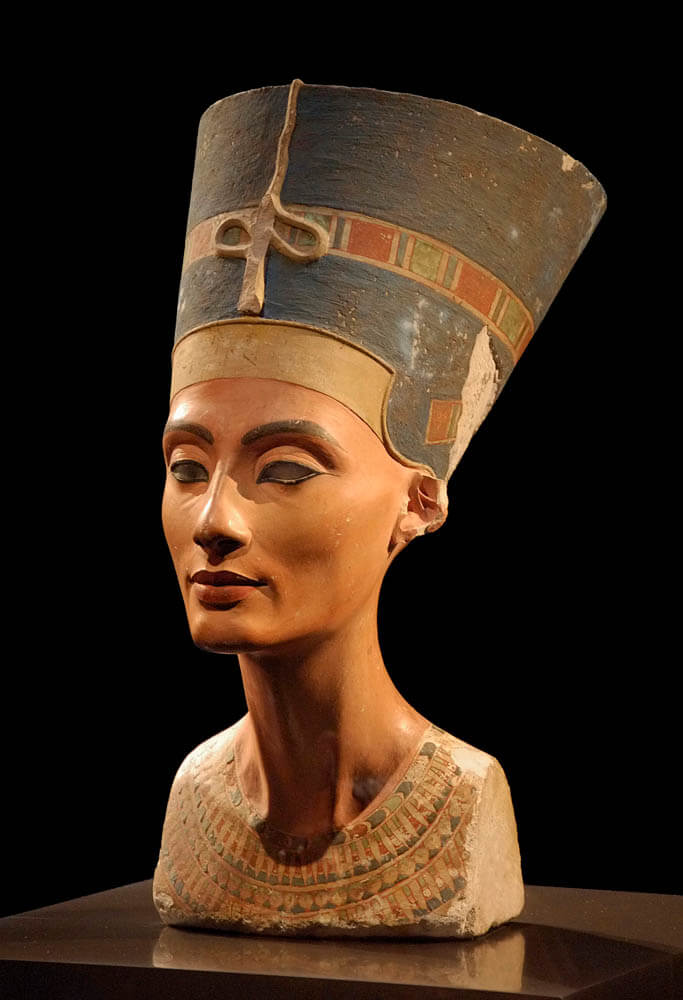

Egyptian statues were created to be placed in tombs or temples and, as a rule, looked at their front side. It is important for the face to look forward, into eternity, and the body viewed from the front should be rigid and vertical, with all the planes intersecting at a right angle. Sometimes there are variations.

For instance, large statues were slightly turned down to the viewer, but examples when the body is bent or the head is turned is very rare in formal sculpture. It is believed that the best craftsmen worked for the king and set a certain artistic level that other sculptors who worked with stone, wood, metal had to match.

Quality was a desirable parameter, but it did not really matter, since until the name of the deceased was written on the statue, it was identified with him. In fact, you could take the statue and change the inscription, substituting another name. This practice was common, and even kings often usurped statues ordered by earlier rulers. It was also believed that it was possible to destroy the memory of the feared or hated predecessor, removing the titles and names from the sculpture. This happened to many statues of Akhenaten, and Hatshepsut names were erased by Tuthmosis III.

Development and History of Egyptian Sculpture

Despite the wealth of materials and number of objects, Egyptian sculpture has evolved over time, so that it is not easy to trace its exact evolutionary path – we see fully developed art from the earliest dynasties. Even at this early stage, Egyptian three-dimensional artists demonstrated mastery in bronze and hard-stone sculpture, and there is no prototype or archaic period to illustrate how this skill was achieved.

Egyptian culture hasn’t yet enlightened us as to prehistoric art forms, and we do not know anything about the previous foreign idiom or skills it could have borrowed, with the exception of the art of Mesopotamia in modern Iraq. Thus, in general, regardless of its origin, Egyptian art in the historic period is more distinguished by its continuity than evolutionary changes. Nevertheless, Egyptian sculpture may differ to some extent from period to period.

Egyptian Sculpture: Examples That Survived

Egyptian sculptures and reliefs can be seen in the temples of Thebes, Abydos, Edfou, Philae, Esneh, and Ipsamboul; in the tombs located around Beni-Hassan, Memphis, and Thebes, and especially in the Museum of Gizeh.

Important collections of statues from ancient Egypt are exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the Louvre in Paris; the Vatican in Rome; the Museo Archeologico in Florence; the British Museum in London; the Museo Egizio in Turin and the Royal Museum in Berlin.

Other collections in America can be viewed at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles; the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia; the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Johns Hopkins University.